Explore Somaliland’s decades-long quest for recognition. This analysis examines legal arguments, historical treaties, African Union dynamics, and strategic geopolitics shaping Somaliland’s statehood in the Horn of Africa

For more than three decades, the Republic of Somaliland has governed itself like a state in every practical sense: a functioning government, multiple transfers of power through competitive elections, a cohesive security sector, and borders tracing back to the final days of the British protectorate. Yet not a single UN member has formally recognized it.

International officials often describe Somaliland as “a paradox of statehood,” an entity that meets virtually every criterion used to define a modern state but remains locked out of the international system it has tried to emulate.

“Recognition is not a matter of capacity,” said one senior Somaliland diplomat. “It is about politics that have little to do with us, and everything to do with the African Union and global geopolitics.”

As momentum builds in 2025 — driven by shifting U.S. strategic interests, Ethiopia’s growing assertiveness, and increasing pressure within the AU — Somaliland’s case illustrates how legal arguments alone rarely tip the scales. But those legal arguments, long overlooked, may now be shaping the conversation more than at any point since 1991.

A State in All But Name

Somaliland restored its independence in May 1991 after the collapse of Somalia’s central government and the brutal civil war in the 1980s that killed tens of thousands in the northwest. In the ashes of that conflict, clan elders convened at the 1991 Burao Conference to revoke the 1960 union with Somalia and reconstitute the short-lived Somaliland state that existed for five days after British withdrawal.

Since then, Somaliland has maintained a level of stability rare in the Horn of Africa. It operates ministries, runs schools and hospitals, manages airports and ports, issues its own currency, and upholds an independent electoral commission.

International observers routinely describe its elections as competitive and peaceful. “It is the most democratic territory in the Somali-speaking world,” said one AU official involved in earlier fact-finding missions.

In 2005, that AU mission delivered one of the most consequential but least acted-upon statements in the history of the organization, calling Somaliland’s case “historically unique and self-justified,” adding that “the situation is not a case of secession but of a failed union.”

Despite the report’s language, AU heads of state buried the issue, fearing that opening the door to Somaliland might trigger a wave of secessionist claims across Africa or undermine the OAU’s founding principle of respecting colonial borders.

Somaliland officials counter that this principle is precisely why they should be recognized. “Our borders are the 1960 British protectorate borders,” Somaliland’s president repeatedly states. “They are colonial borders. The AU’s fear does not apply to us.”

Diplomacy Without Recognition

Somaliland’s foreign policy over the past two decades has followed a dual track: strengthening domestic institutions to demonstrate statehood while aggressively seeking bilateral partnerships that implicitly acknowledge its sovereignty.

Those efforts accelerated between 2023 and 2025.

The Ethiopia–Somaliland MOU

In early 2024, Ethiopia and Somaliland signed a landmark memorandum of understanding granting Ethiopia access to the Berbera port, rights to establish a naval facility, and a potential stake in Ethiopian Airlines. While the full details remain partly confidential, Ethiopian officials acknowledged that recognition of Somaliland was explicitly part of the long-term arrangement.

“It is not a secret,” said an Ethiopian official familiar with the negotiations. “Ethiopia needs diversified access to the sea. Somaliland needs recognition. The MOU aligns these interests.”

The agreement provoked sharp backlash from Somalia, which called it an “act of aggression,” and from the AU, which urged restraint. But it also signaled that recognition might no longer be an abstract debate.

Gulf Engagement and Global Visibility

Somaliland’s expanding ties with Gulf States — primarily the UAE — have offered another avenue to legitimacy. Dubai’s DP World has invested heavily in upgrading the Berbera port, and Somaliland received an invitation to the 2025 World Governments Summit, placing it alongside recognized states in high-profile panels.

“Visibility is part of recognition,” said a foreign policy adviser in Hargeisa. “Every stage that places Somaliland next to other nations normalizes us.”

Somaliland also maintains an ongoing observer bid with the Commonwealth, although political hesitancy in London has stalled progress.

AU Deadlock

At the African Union, the issue remains frozen. Proposals to formally table Somaliland’s recognition — including a 2019 effort supported by several East African states — have failed to gain traction. AU diplomats privately cite fears of setting a precedent that could encourage breakaway claims in Nigeria, Cameroon, or DRC.

One senior AU official, speaking on background, said: “The legal case for Somaliland is stronger than most observers realize. But recognition is not decided in legal seminars. It is decided in the heads of state summit hall.”

A New Variable: Washington

By late 2025, movement in Washington is upending long-standing assumptions.

Under President Trump, U.S. policy has increasingly linked Somaliland to broader strategic concerns in the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa — specifically countering Chinese influence around Djibouti, home to China’s first overseas military base and a critical node in Beijing’s Belt and Road strategy.

Project 2025, a conservative policy blueprint influential in shaping Trump’s second-term agenda, explicitly identifies Somaliland as a candidate for deeper security cooperation and potential recognition. Discussions between U.S. defense officials and Somaliland have focused on expanded access to the Berbera airfield — one of the longest runways in Africa and a Cold War-era U.S. installation.

“Somaliland is a strategic asset,” said a former U.S. Africa Command officer. “It sits on the Gulf of Aden, faces Yemen, and provides a stable alternative to Djibouti. The politics have delayed U.S. action, but the strategic case is overwhelming.”

Somaliland’s president, after high-level discussions with U.S. officials this year, told reporters that “recognition is on the horizon,” language that would have been unthinkable a decade ago.

Insiders suggest the U.S., U.K., Israel, UAE, and as many as 17 other states are drafting bilateral frameworks that would enable more formal steps toward recognition between 2026 and 2028.

But as of December 2025, no state has formally crossed that threshold.

The Legal Case: A Sovereign State by Every Standard

While recognition is political, Somaliland’s legal arguments have become increasingly central to its diplomatic messaging — and quietly influential among international lawyers and foreign ministries.

Montevideo Convention Criteria

Under the Montevideo Convention (1933), widely seen as the standard definition of statehood, an entity must have:

- a permanent population

- a defined territory

- a government

- the capacity to enter into relations with other states

Somaliland meets all four.

“We don’t need recognition to be a state,” said a Somaliland legal adviser. “Recognition acknowledges reality; it doesn’t create it.”

International law scholars generally agree that Somaliland satisfies the Montevideo criteria more clearly than several UN-recognized states that achieved statehood through political support rather than legal pedigree.

Restoration, Not Secession

Somaliland’s second argument is historical: its 1991 declaration was not secession from Somalia but restoration of the independence it held between June 26 and July 1, 1960 — a fact supported by contemporary UN records.

The union with Italian Somalia, Somaliland argues, was never properly formalized. No binding union treaty was deposited at the UN. Somali lawmakers in Mogadishu approved a different text than Somaliland’s parliament in Hargeisa. The two sides never ratified a single, identical instrument.

“Legally, the union was defective from day one,” said a British historian specializing in decolonization law. “Somaliland’s argument is not without precedent.”

Self-Determination

Somaliland also invokes the right to self-determination under the UN Charter and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, pointing to:

- mass atrocities committed by the Siad Barre regime

- the near-total destruction of Hargeisa

- overwhelming public support for independence expressed in the 2001 constitutional referendum

The AU Principle of Colonial Borders — Supporting Somaliland, Not Somalia

The AU’s most sacrosanct doctrine — uti possidetis juris, preservation of colonial-era boundaries — has often been cited to oppose Somaliland’s case.

But Somaliland argues the opposite: its borders are exactly the borders the British left in 1960.

“If colonial borders are to be preserved,” said a Somaliland official, “then recognize them.”

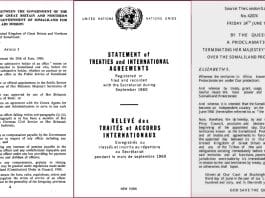

The Underappreciated Evidence: UN Article 102 Deposits

One of the most unusual — and increasingly cited — elements of Somaliland’s argument lies in UN Article 102, which requires UN member states to register treaties with the United Nations for them to be legally invoked.

Somaliland Deposited Treaties as a Sovereign State in 1960

The UN Treaty Series contains multiple agreements deposited on June 26, 1960, the day Somaliland became independent:

- Interim Agreement for a United Kingdom Aid Mission (UNTS No. 5346)

- Exchange of Letters on Independence (UNTS No. 5349)

- Public Officers Agreement (UNTS No. 5347)

- Somaliland Scouts (Defense) Agreement (UNTS No. 5348)

- East African Currency Board Exchange (UNTS No. 5350)

- Treaties and international Agreements (UNTS Volume 374 sequence)

The UN Secretariat only accepts deposits from sovereign states or entities meeting the criteria for treaty registration.

“That record alone demonstrates that the UN viewed Somaliland in 1960 as a sovereign state with treaty-making authority,” said a former UN legal officer.

No Union Treaty Deposited

Equally significant: no Somalia–Somaliland union treaty was ever registered with the UN.

Under Article 102, unregistered treaties cannot be invoked before the UN.

“One can argue the union lacked international legal effect,” said an international law professor. “It existed politically, but not juridically.”

Practical Impact

Article 102 deposits do not grant recognition. They do, however:

- support Somaliland’s claim to restored sovereignty

- demonstrate international legal personality in 1960

- undermine Somalia’s assertion of a fully valid, perpetual union

- bolster Somaliland’s standing in any future ICJ advisory opinion or AU legal review

Several foreign ministries privately acknowledge that these documents carry significant evidentiary weight.

Why Recognition Still Hasn’t Happened

Despite legal clarity and growing geopolitical interest, recognition remains stalled for three main reasons:

1. African Union Reluctance

AU leaders fear setting a precedent that could destabilize fragile borders on the continent, even though Somaliland’s claim fits squarely within colonial boundaries.

2. Somalia’s Opposition

Somalia, though lacking effective control over Somaliland since 1991, asserts territorial integrity. No African state wants to be seen overriding another’s territorial claim.

3. Geopolitical Timing

Major powers — chiefly the U.S. and U.K. — are weighing recognition against broader regional alliances, counterterrorism partnerships, and Red Sea tensions.

Recognition, one Western diplomat said, “is not about law or capability. It is about timing.”

A Turning Point Approaches

The strategic calculus in the Red Sea region is changing quickly.

U.S. officials quietly acknowledge that a future military cooperation agreement at Berbera could force Washington to confront the recognition question more directly. Ethiopia appears ready to move sooner, though likely not before its 2026 election cycle. Gulf States are watching both closely.

Somaliland officials believe their long wait may be nearing an end. But after 34 years of unrecognized statehood, caution runs deep.

“We have survived without recognition,” said a senior Somaliland minister. “We would like the world to acknowledge reality. But our legitimacy does not depend on it.”

Whether 2026, 2028, or later, the trajectory of Somaliland’s diplomacy suggests that the question facing the world is no longer whether Somaliland constitutes a state — but when the political barriers to admitting that reality will finally fall.