The U.S. intervention in Somalia is not remembered fondly, but it saved thousands of lives.

On the eve of Thanksgiving in 1992, then-U.S. president George H. W. Bush, in his final weeks in office, approved a major military intervention to relieve a humanitarian crisis in Somalia.

After losing his bid for re-election, Bush was not expected to make any dramatic foreign-policy decisions; lame ducks rarely quack or take unexpected steps. But the first president Bush did.

Today, we vividly remember the chain of events during the Bill Clinton presidency that led to the American withdrawal from Somalia in 1994—the shot-down Black Hawk helicopters, the body of a U.S. soldier dragged through the streets of Mogadishu, the angry crowds taunting American military personnel. We sometimes forget that those tragic events were preceded by a successful mission that saved lives in a war-torn nation on the brink of self-destruction.

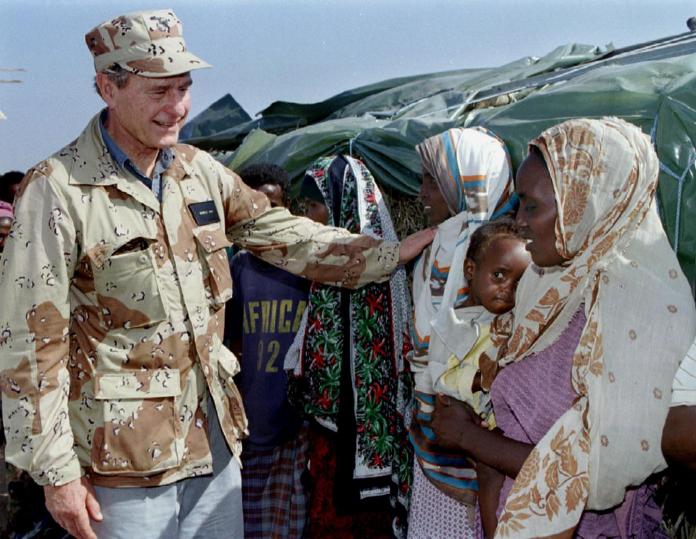

RICK WILKING/REUTERS

In the early 1990s, a bitter civil war freed the people of Somalia from a brutal dictator, Siyad Barre, but failed to re-establish order and stability when clan leaders and their militias fought over succession. A combination of civil war, clan conflict, refugee dislocation and drought left the nation unable to feed its population. The emergency generated a routine international response with shipments of food, medicine and relief workers making their way to the country. But continued fighting, particularly in the south and the capital Mogadishu, was so pervasive that the effective distribution of aid was impossible.

When then U.S. Ambassador to Kenya, Smith Hempstone, visited refugee camps on the border with Somalia in the summer of 1992, he described his visit in a memo to Washington titled, “A Day in Hell.” In Somalia, hellish starvation and malnutrition were rampant, and as with every famine, the first to die were the young, the old and the infirm. An estimated one in four children under the age of five years old died in the famine, according to some estimates.

In August 1992, the U.S. began an airlift of food and medicine to the southern regions that were inaccessible to relief convoys. These supplies made a difference, but far too often food was captured on the ground by armed groups, who hoarded it and used relief packages as a currency in the crippled Somali economy. Journalists who were able to get to the refugee camps and remote locations within Somalia came back with harrowing stories and pictures of desperation.

The pictures made their way to television screens, first on CNN—where more resources were devoted to the Somalia story—and then more broadly across the media landscape. Two days before Thanksgiving, on the night before President Bush made his decision to send over 28,000 US troops, NBC broadcast heart-wrenching black-and-white photographs of starving Somali children. Tom Brokaw told his viewers: “In Somalia, children under the age of five have all but disappeared…. It’s a place where a thousand die today, and a thousand will die tomorrow, and the day after that, and the day after that.”

The vivid media coverage gave rise to what came to be called the ‘CNN effect’—the theory that widespread media coverage can influence foreign-policy decisions. With this came the suggestion that the U.S. military intervention was the product of excessively emotional public and presidential reaction to images of suffering and starvation.

There is some truth to that conclusion, but less than many commentators recognize. The wheels of government move slowly and it was not a sudden and surprising presidential decision the day after the NBC broadcast that turned everything around. The staff planning in the Pentagon for possible military action began weeks before the final presidential decision. During those weeks, State Department memorandums made the case that only a U.S. intervention could quickly end the famine. Members of Congress and newspaper columnists lobbied for action.

Bush had a long-term interest in the Somali situation and a consistent desire to do something about it. He ordered the airlift in August, then a full-scale intervention in November after the election. Those who knew him well thought of him as a humanitarian who would surely offer U.S. assistance if the risks to our military forces were deemed acceptable.

When the marines landed in Somalia, there were television cameras on the beach and no serious resistance. Explicit diplomatic warnings and the arrival of an overwhelming military force cowered the clan leaders and allowed for the rapid distribution of food and medicine. Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger later told me that the U.S. helped the people of Somalia because it was right, and because it could.

Memories of the Black Hawks being brought down make people think of Somalia as being a U.S. foreign-policy failure. It wasn’t. Tens–perhaps even hundreds–of thousands of lives were saved by the American protected distribution of aid. For Somalia in the final weeks of 1992, there was a very real reason for Thanksgiving.

Robert Strong is a professor of politics at Washington & Lee University in Lexington, Virginia.